If you walk into any running store or performance lab that does a gait analysis of your running form, you will always find one humble machine: the treadmill. I’m a biomechanist and a former running store employee, so I’ve used a treadmill or two to assess running form. While I can’t watch how all of you run or review video footage, I can help you make your own assessments and adjustments.

Though this guide promises to teach you how to run properly, you likely have all of the most important building blocks already. In fact, if you aren’t injured or in pain when you run, you could stop reading right now (but then you would miss a bunch of cool running facts).

Bio

When I make an assessment of someone’s running form, I like to take a history of their running experience. Since I can’t hear yours, here’s mine instead.

I have been a runner since 2009 when I took up cross country in middle school. I competed on a D2 collegiate team in cross country and track.

After collegiate competition, I received my master’s degree in biomechanics, where I focused on running form and shoes for my research. I continued training and found a new passion in reviewing and testing treadmills. I have continued running, completing two marathons and an ultramarathon. I am currently training for my first Boston Marathon.

I use both treadmill running and outdoor running to train for road races. If you are training for an outdoor running event, like me, you might wonder how useful training on a treadmill is for a road race, so let’s look at some of the differences.

Is Treadmill Running Different From Outside Running?

Biomechanists study two main categories of endurance running: treadmill and overground running. It has long been debated whether they are actually the same. Can you study runners on a treadmill and generalize that to runners off a treadmill (overground running)?

The answer is yes, kind of. We change every step we take based on sensory information from our environment. What we expect the surface underfoot to feel like and our past experiences with similar surfaces change how our muscles contract when we land and what position our foot is in.

When you run on a treadmill, the treadmill console, motor hood, and the end of the running deck are visual information that tells your body to use a shorter stride to avoid running into the treadmill or falling off. As you grow more comfortable with the treadmill, you may lengthen your stride again.¹

There are minimal differences between my outdoor running form (right) and my treadmill running form (left.

A treadmill is usually softer than running on pavement outside, so your body also adjusts to that.² When we run outside, our bodies have to cushion each step, whereas the treadmill provides cushioning when you run on it.

I could see this cushioning for myself when I recorded my leg spring stiffness (a measure of running mechanics impacted by surface stiffness) while running on a paved path and on a very soft treadmill.

Leg Spring Stiffness

What is leg spring stiffness (LSS)? It is a measurement of our running mechanics modeled as a spring. It uses kilonewtons per meter to describe our body’s stiffness (or ability to compress) when it is modeled as a spring. It is NOT a measurement of how stiff or achy your legs are after a run or workout.

Think of a slinky. It is not a stiff spring. When it is stretched out long, it is very easy to squish it down. If the slinky represented a runner, it would have a low leg spring stiffness. It takes very little force (kilonewtons) to compress the slinky (or change its length in meters).

We could also have a very stiff spring, like in a pogo stick. You couldn’t compress it very easily with your hands. It takes a big bounce with your full body weight to compress the spring all the way down.

Now, our body can change how stiff it behaves. Typically, our bodies want to keep the entire running “system” consistent. The running system includes your body, your shoes, and the ground.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s ignore running shoes. I used the same running shoes to collect my data, so since it is a controlled variable, we can forget about it for now. Instead, we can focus on the runner (me) and the ground.

We can also think about ground cushioning or softness as a spring. If you push down on the concrete, does it move at all? Probably not. If you push down on a mattress, it will move significantly more.

If the concrete compresses 0 inches and the mattress compresses 4 inches, a runner landing on both of these surfaces would have to compress 5 inches and 1 inch, respectively, to keep both systems the same.

Ground: 0 + 5 = 5

Mattress: 4 + 1 = 5

So, when the ground is very stiff (concrete), the runner has to be much softer. When the ground is soft (mattress), the runner has to be a lot stiffer to keep the system’s total the same. Now, runners can’t compress like springs, but this visual simplifies what happens with energy stored within the muscles, so we can imagine the runner as a spring.

Another way to describe leg spring stiffness is to say that it describes the amount of force necessary to compress the spring (the runner’s leg) one meter. So, a higher leg spring stiffness means the runner’s leg is stiffer and requires more force to compress. A low leg spring stiffness means the runner’s leg is less stiff (softer) and requires less force to compress.

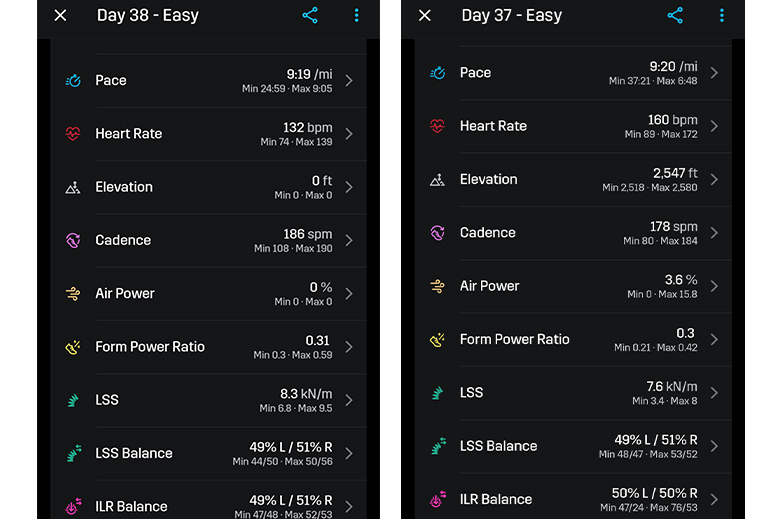

Below, I have included a screenshot of my running data from my Stryd running pods that shows my leg spring stiffness (LSS) is higher when running on the treadmill than it is when I am running outside. My average speed is about the same, and I wore the same running shoes for both trials. These are also consecutive days.

LSS (leg spring stiffness) is shown for the treadmill (on the left) and on the pavement (on the right) for two consecutive running days.

From this data, we can infer that the treadmill running surface is (probably) softer than the pavement (outdoor) condition.

Leg spring stiffness can change within a single step. So, if you are running along a paved trail and veer off into the grass and then back onto the trail, your LSS will change to match every surface change very quickly.

While it is cool to see how our bodies respond to different surfaces, it is a subconscious change. You do not have to try to change your leg spring stiffness. You can let it change on autopilot! Lastly, differences in leg spring stiffness will probably not be observable to the naked eye.

Treadmill Running vs. Outdoor Running: Summary

In summary, treadmills change our running form but not consciously. Unless you have a really short or narrow treadmill running area, you don’t need to change your running form specifically for the treadmill. When I train on a very small treadmill, I have to be more mindful of my stride length, but that’s the only time I’m making an intentional change for the treadmill.

Treadmill running does not require a unique running form because it is so similar to overground running. In fact, we may be even better at treadmill running than outdoor running because we don’t have to deal with as much air resistance.

Now that we know we can use the same running form, whether running on a treadmill or outside, we can learn how and when to use a treadmill to improve our overall running form.

When To Use a Treadmill to Learn Better Running Form

Source: AI Generated. Shutterstock

If you are a healthy runner without any pain or injuries, you probably don’t need to change your running form. If you are hoping to get faster or become more efficient, we will talk about what you should do later, but for now, don’t think about trying to make specific changes.

Our bodies have preferred movement patterns. Each of our preferred movement patterns for running looks different, but that’s okay. We don’t need to change that. Some elites have “bad running form,” but that doesn’t get in the way of their performance.

Running on Treadmill

Running can be pain-free, but painful running can also be a symptom of other issues. Are you doing too much too soon? Are you new to running and still building the strength to handle each impact? Sometimes, running less, and sometimes, running more is the simple answer.

Yet, if you are injured or in pain, fixing your form could help. Below, we will look at how to change your form safely and what to do first.

What If Running Outside Hurts But Treadmill Running Doesn’t?

Treadmills provide a softer, more consistent running surface than outdoor running. Aches and pains experienced only outside and not when running on the treadmill could be caused by the added stress of running on a harder surface. If your feet are sore or you think you are experiencing shin splints, this may be the case.

Running Outside

You could try running on a softer natural surface like grass, sand, or dirt. If you want to run on the pavement, try reducing the distance and time of your outdoor runs and slowly build up your outdoor running mileage. Warming up properly before outdoor runs can also help.

If you are training indoors, there are ways to work on your running form to prepare for outdoor exercise. While I recommend strength and mobility training primarily, let’s dive into how you can use your treadmill to make the changes you desire.

How to Change Your Running Form Using Your Treadmill

So, you want to change your running form using your treadmill? I’ve outlined a simple process below to help you make the transition.

Before you get started, you might need to gather additional equipment. To complete the steps below, you will need a camera. If you have one that can shoot in slow motion (at a higher frame rate), that’s even better. Then, you can ask a friend for help or mount your camera with a tripod or other method of propping it up.

Assessing Sydney’s Running Form

1. Take a video of your current running form. You can prop up your phone or camera next to your treadmill. Take a video with your whole body in the frame and then a video focusing on your lower legs and feet. If you have other problem areas, like your hips or arms, you could also take a video focusing on those areas.

2. Identify problem areas by looking for asymmetries or evaluating what is happening in the area causing your pain. Ideally, you should consult a running coach or physical therapist who can better interpret the video.

3. Once you have identified one problem area, work on that area. It is too overwhelming and often counterproductive to address every fault at once.

4. Start incorporating your change into your runs. Make a conscious effort to use the correct running form, using video to validate your success. If you feel your form slipping, end your run. As you practice your form, you will be able to hold it for longer until you reach your desired mileage.

5. Support your form change with form drills and even barefoot running. Manual treadmills are great for barefoot runs! If you are trying to switch to a midfoot strike or decrease the force of each step, running barefoot helps.

Common Running Form Problems You Can Fix On Your Treadmill

The following running form problems are some of the most common. Please remember that I only consider these running form characteristics to be problems if they present with pain or injury.

Our bodies develop from a young age to cope with certain movement patterns and build strong bones, tendons, and ligaments around those patterns. Breaking a pattern that is comfortable and suitable for your body could create more problems, injuries, and, ultimately, a setback to your running because it has not developed over the years for this new movement pattern.

Running Too Tall or Slouching

If I keep running like this, my center of mass might not move much, but it isn’t actually that efficient.

Running too tall can put a lot of stress on your hip flexors. Your motion is directed vertically, so you may also bounce up and down much more. You are not executing the forward lean properly if you are slouching or leaning forward from your spine or hips.

Often, correct form is taught by imagining a string attached to your head, pulling you straight up. Then, add a slight forward lean at the ankles. You should almost feel like you are “falling” into each step. Try moving further back from the treadmill console to give yourself room to lean forward.

Leaning Forward

Note: Increasing your forward lean may not be appropriate for runners with knee pain.³ There are risks involved with making even small changes to your running form, and leaning forward could apply more pressure to your knees. It is especially important to ensure you are not leaning from your waist but from your ankles.

Feet Turned Outward

If you walk with your feet externally rotated, there’s a good chance you run this way, too.

If your toes point to the outside rather than straight forward as you run, you could have weak arches. This gait pattern is also common in runners who do not have a good hip or knee range of motion. If you can, restore the range of motion to your affected knee or hip. Often, there is pain in one of these joints with this form mistake. If there isn’t pain, it probably does not need to be fixed.

You can also try consciously turning your toes forward when running, but you should also change how you walk and stand to reinforce it. (How would your feet look if you stood up straight right now?) Strengthening your arches and intrinsic foot muscles is also beneficial, as runners with this form mistake may have “flat feet.”

Making this form correction on a treadmill is beneficial because you can acquire video evidence of whether or not your form change is effective. You can also look down at your feet without worrying about walking into traffic.

I often spotted this form issue when taking videos of runners’ forms at the running shoe store where I worked. It was a super quick and easy fix to recommend. Make sure you take a good video from a few angles (side, front, and back) at foot level.

Close Up on Feet Turned Out

Note: Many runners and walkers have this type of walking and running form without issue, so fixing it is unnecessary. It is also important to note that bringing your feet into a neutral (forward-pointing) position could cause pain in the joint (hips or knees) where the range of motion is limited. Thus, starting with mobility work and improving strength may be better than correcting your form.

Additionally, it is not uncommon to experience pain in the bottoms of your feet as you adjust to the new position and weight distribution across your feet.

Feet Turned Inward

Internal rotation may be a sign of a limited range of motion at the foot or ankle.

If you run with your toes pointing inward or pigeon-toed, restoring mobility in your ankle joint with exercises like calf stretches and ankle circles is helpful. Runners whose feet turn inward often present with high arches. Like runners who turn their feet outward, these runners should only make form changes if they are currently presenting with pain.

This one might be harder to spot in your treadmill running video. If you have high arches, it could be a sign that you tend to run this way. You could also try to stand naturally and where your feet naturally turn. Many people who run with their feet pointed in or out stand the same way.

Note: Many runners and walkers whose feet are turned inward have moved this way their entire lives. If no pain or injury exists, changing the foot alignment could strain muscles and connective tissue that developed to cope properly with the original gait pattern. I recommend first starting with strength and mobility training to address any underlying issues.

Knees Pointing Down and Exaggerated Kick Back

Your knees may not come very far forward at slow speeds, but we do want to reduce this exaggerated kick back.

If your knees are facing the ground and your foot is kicking really far back, try strengthening your hip flexors with leg raises. Think about running with high knees and using your hips to bring your legs up with each stride.

Add 30-second bouts of running with higher knees while keeping the same paces during your runs. If you are on the treadmill, move further from the console to give yourself enough room. Many runners may be more comfortable executing this drill outside with more room.

Remember, you are not doing a “high knee” drill where you lift the knees as high as possible. Instead, simply bring the knees up slightly higher than normal, but otherwise, keep your natural running gait.

Many runners with this form mistake are running with a low cadence. Try increasing your running cadence and practicing leg turnover drills, like skips, fast feet, and high knees.

Knees Down

Landing Hard / Loud Feet

I have a notoriously loud foot strike despite all my efforts to land more quietly.

Are you a super loud runner? Can everyone hear you running from a mile away? This form issue could be due to your running shoes; however, you can also try landing more softly. Run like you are trying to sneak up on someone. This strategy can reduce the impact of each step, leading to less stress on your legs.

If you are on a treadmill, can you hear your feet over the treadmill motor? Try to quiet them as much as possible, but note that treadmill cushioning and shoe cushioning can also change how noisy you are, even if your running form doesn’t change.

Landing Hard

The One Running Form Fix I (Might) Recommend to Everyone

Run with a cadence of 180 spm or higher.

That’s it.

Source: AI Generated. Shutterstock

That is the one running form fix that I recommend to everyone, and it is so easy to do it. It’s low risk and could improve a bunch of other things, like running economy, impact force, and overstriding⁴᠈ ⁵.

Since treadmills tend to increase your running cadence, it may be easier to adjust your running form by starting on the treadmill. It’s also easier to do when running on a flat surface, as provided by the treadmill. Our hips can get fatigued from using a higher cadence, but running on the treadmill gives you good practice to prepare for outdoor training with this technique.

If you have a watch or other fitness tracker that records your running cadence/steps per minute, see what you have been hitting. Check your fast runs and your slow runs. If you are below 175, this fix is for you. If you are below 170, you might have to start with building up to 170 spm before progressing to 180 spm.

I also recommend checking if you take fewer steps per minute if you speed up. I’m guilty of this form mistake, so be sure to practice a higher cadence at different speeds. Our step rate should naturally decrease as we slow down and increase as we speed up. If we notice that this is not happening, we could be relying on overstriding to run at a faster speed.

I’m setting up my watch to vibrate and beep at 180 beats per minute.

You can use a watch or a metronome phone app to keep you on track. If your treadmill and footsteps are loud, pair your metronome to your treadmill’s speakers if it has them. Set the metronome to 180 and try to keep up with the beat. My Garmin has a metronome option in the activity settings, so try it if you have one!

When moving from the treadmill to outside training, continue to use a metronome to reinforce this technique in the new environment. If you have a Garmin or other fitness tracker that measures running cadence, check your running data intermittently to see if you are able to keep up the proper technique.

Because taking more steps per minute to run at the same speed shortens your stride, it should help with overstriding. Often, when runners want to switch from a heel strike to a midfoot strike, their problems might be from overstriding. So, try making this switch first.

Increasing your running cadence can help you develop the turnover speed necessary to run faster, decrease vertical oscillation, and reduce the total force of each step. Thus, it is a good place to start when adjusting your running form.

Should I Change My Footstrike?

My regular foot strike is a midfoot strike. Here, I am exaggerating it slightly for the camera.

One morning, I was running along my usual route when an old man yelled at the runner ahead of me, “Stop running on your toes! Watch the Olympic marathon runners! They don’t do that!” I was in a hurry, so I didn’t stop to talk about that, though the biomechanist in me wanted to.

Luckily, he didn’t notice I was also running with a midfoot strike, so I finished my run.

Midfoot Striking

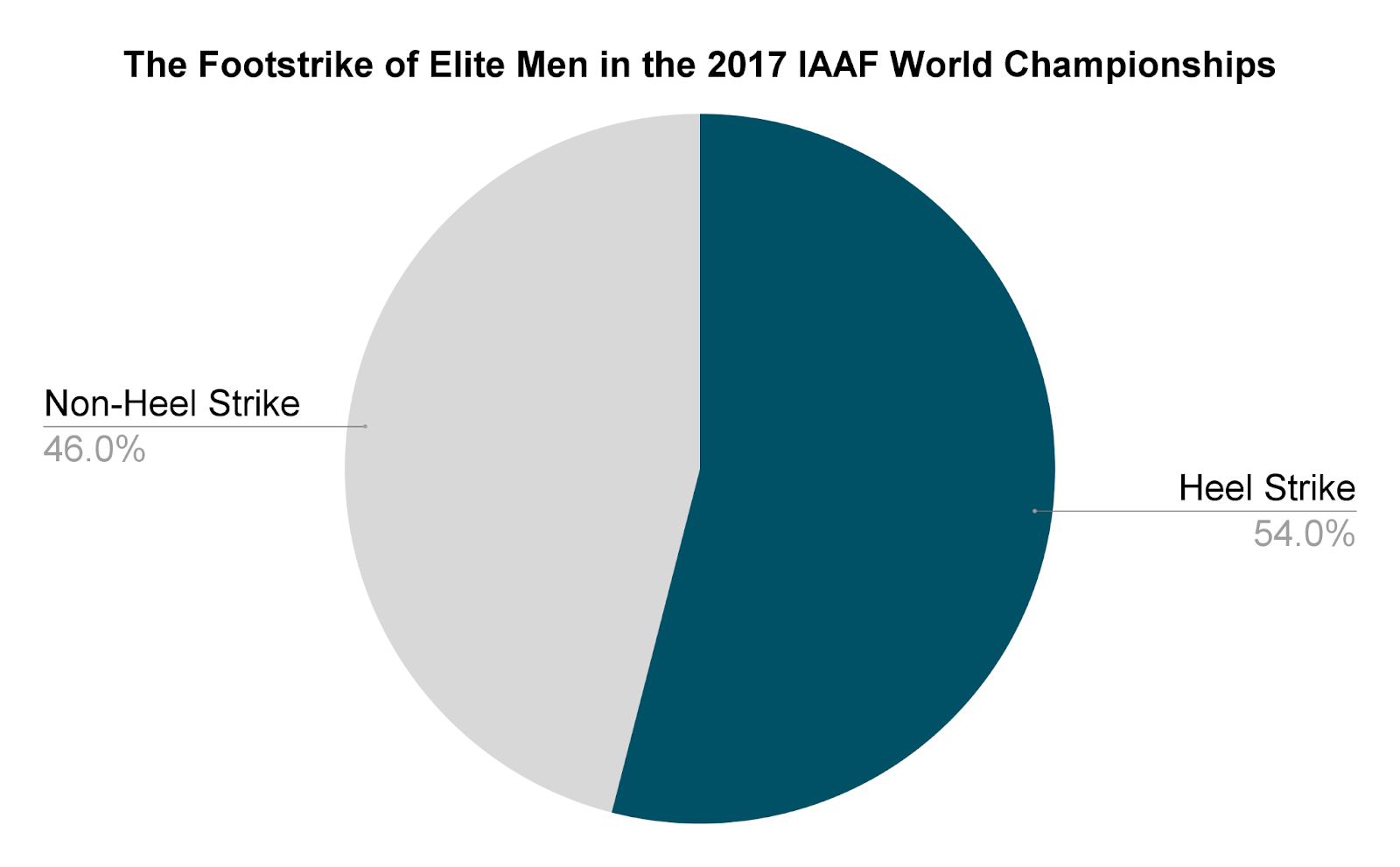

While I don’t typically accost runners about their running form, I did have something in common with that impromptu running coach: I know most elite runners heel strike. At all levels, most distance runners heel strike⁶.

This chart shows the minimum percentage of male runners using a rearfoot strike pattern and the percentage of male runners who used a non-rearfoot strike pattern at any point during the 2017 IAAF World Championships.⁶

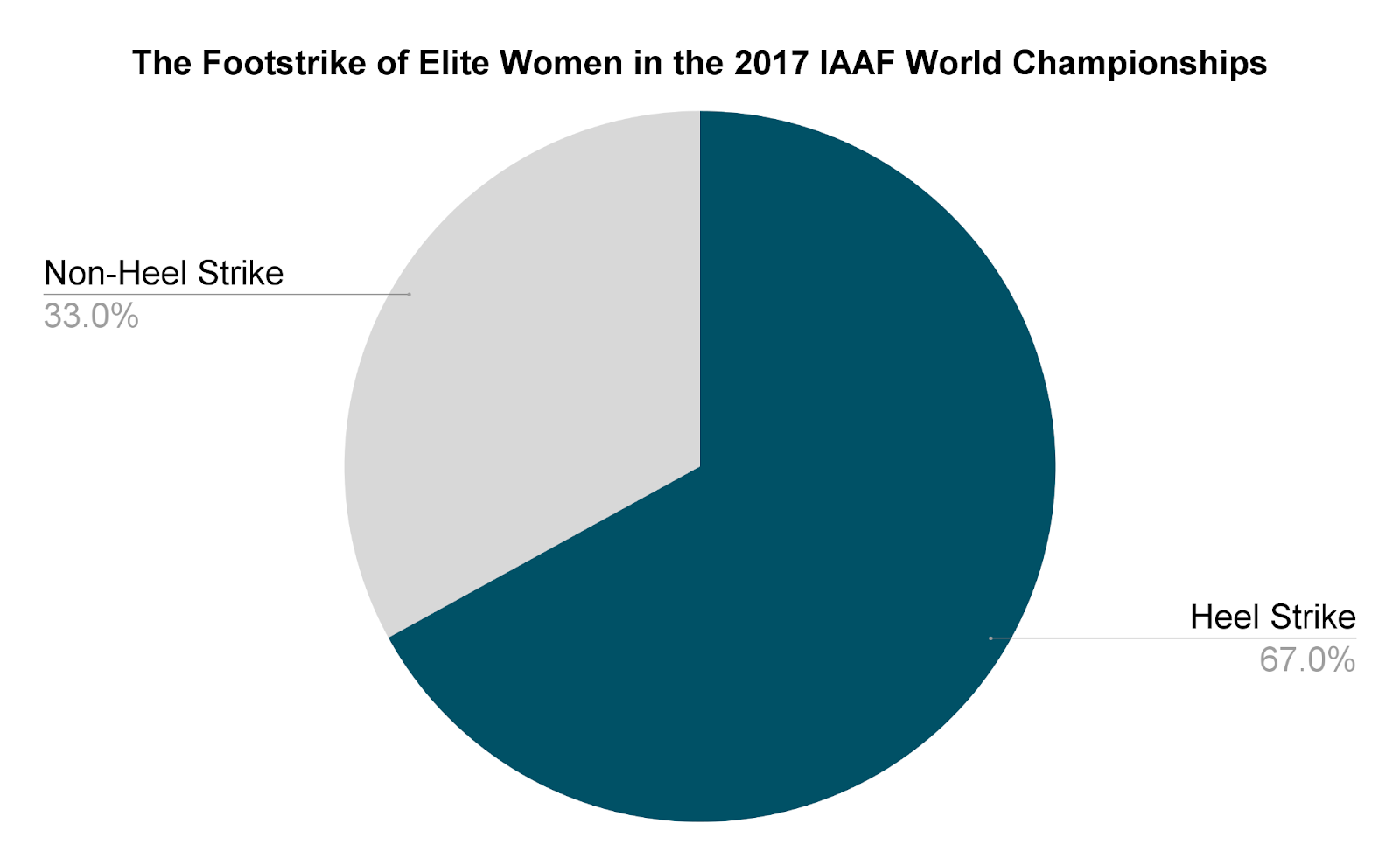

This chart shows the minimum percentage of female runners using a rearfoot strike pattern and the percentage of female runners who used a non-rearfoot strike pattern at any point during the 2017 IAAF World Championships.⁶

Shoes are even designed for heel striking. Contrary to popular belief, it’s really not that bad to heel strike.

Source: Dave Smith. Shutterstock

Brigid Kosgei was the previous women’s world record holder in the marathon (2:14:04), and here, she is using a heel strike during a race.

The difference between landing on your heels and on the balls of your feet might just be which injuries you are prone to. For example, I have had Achilles tendonitis or tendinopathy numerous times now, and the research demonstrates that my midfoot strike pattern predisposes me to this type of injury, while forefoot running leads to higher rates of posterior calf injuries⁷.

I’m running very slowly with a heel strike here. I typically use this foot strike for recovery runs to give my calves a break.

Meanwhile, rear foot striking (aka heel striking) creates an “impact peak” or high force when you land on each step⁸. This force has been linked to increased injury rates, though some research suggests otherwise⁷.

Heel Striking

So, my advice for runners who want to change from a heel strike to a midfoot strike is this: Don’t. Or better yet, learn to use them both.

A Note for New Runners

New runners usually look different from experienced runners. Is that because experienced runners have learned how to run, and beginners haven’t yet? Maybe, maybe not. When children learn to walk, we don’t immediately force them into the correct form, criticizing every deviation from mature walking form. Instead, we let them progress through the typical stages.

Source: ChatGPT, image AI generated

Neither this baby nor ChatGPT can get running form right, so if you are running with your opposite arm and leg forward, you are already a stride ahead.

Running can be a lot like learning to walk. Our muscles, tendons, and ligaments grow stronger with time and practice to support our running form. This is one reason that new runners should progress their mileage slowly, while more advanced runners can typically make larger jumps in mileage. It normally just takes time.

Bottom Line: How To Run Properly on a Treadmill

Whether you are trying to reduce pain and risk of injury or improve performance, changing your running form may be something you consider. However, changing our running form when we are healthy and pain-free is not usually advised. Use strength and mobility training to support being a healthier runner while addressing specific problem areas presenting with pain or injury.

A treadmill is a valuable tool for evaluating running form and making improvements if necessary. The consistent and softer running surface can provide a better environment for changing form than paved paths with uneven surfaces and other obstacles. It also allows you to collect video evidence of how your form currently looks and if it changes as desired.

To conclude, the running form should be changed cautiously. It is best to consult a running coach or other exercise professional who can review your specific running mechanics and running history in person.

References

1. Van Hooren, B., Fuller, J.T., Buckley, J.D. et al. Is Motorized Treadmill Running Biomechanically Comparable to Overground Running? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Over Studies. Sports Med 50, 785–813 (2020).

2. Kerdok, A. E., Biewener, A. A., McMahon, T. A., Weyand, P. G., & Herr, H. M. (2002). Energetics and mechanics of human running on surfaces of different stiffnesses. Journal of Applied Physiology, 92(2), 469–478.

3. Huang, Y., Xia, H., Chen, G., Cheng, S., Cheung, R. T. H., & Shull, P. B. (2019). Foot strike pattern, step rate, and trunk posture combined gait modifications to reduce impact loading during running. Journal of Biomechanics, 86, 102–109.

4. Schubert AG, Kempf J, Heiderscheit BC. Influence of stride frequency and length on running mechanics: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2014 May;6(3):210-7. doi: 10.1177/1941738113508544. PMID: 24790690; PMCID: PMC4000471.

5. Austin CL, Hokanson JF, McGinnis PM, Patrick S. The Relationship between Running Power and Running Economy in Well-Trained Distance Runners. Sports. 2018; 6(4):142.

6. Hanley, B., Bissas, A., Merlino, S., & Gruber, A. H. (2019). Most marathon runners at the 2017 IAAF World Championships were rearfoot strikers, and most did not change footstrike pattern. Journal of Biomechanics, 92, 54-60.

7. Hollander, K. , Johnson, C. , Outerleys, J. & Davis, I. (2021). Multifactorial Determinants of Running Injury Locations in 550 Injured Recreational Runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53 (1), 102-107. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002455.

8. Cavanagh, P. R., & Lafortune, M. A. (1980). Ground reaction forces in distance running. Journal of Biomechanics, 13(5), 397–406.

АРХИВ

АРХИВ БОКС И ЕДИНОБОРСТВА

БОКС И ЕДИНОБОРСТВА Игровые виды спорта

Игровые виды спорта КАРДИОТРЕНАЖЕРЫ

КАРДИОТРЕНАЖЕРЫ МАССАЖНОЕ ОБОРУДОВАНИЕ

МАССАЖНОЕ ОБОРУДОВАНИЕ МЕДИЦИНА РЕАБИЛИТАЦИЯ

МЕДИЦИНА РЕАБИЛИТАЦИЯ СВОБОДНЫЕ ВЕСА

СВОБОДНЫЕ ВЕСА СИЛОВЫЕ ТРЕНАЖЕРЫ

СИЛОВЫЕ ТРЕНАЖЕРЫ Соревновательное оборудование

Соревновательное оборудование СПОРТ ДЛЯ ДЕТЕЙ

СПОРТ ДЛЯ ДЕТЕЙ СПОРТИВНОЕ ПИТАНИЕ И АКСЕССУАРЫ

СПОРТИВНОЕ ПИТАНИЕ И АКСЕССУАРЫ УЛИЧНЫЕ ТРЕНАЖЕРЫ

УЛИЧНЫЕ ТРЕНАЖЕРЫ ФИТНЕС И АЭРОБИКА

ФИТНЕС И АЭРОБИКА